Indonesia is under threat of food insecurity and undernutrition, and faces “alarmingly high” stunting levels. In 2007, an estimated 7.7 million children under five were stunted, according to the Food Security Portal.

And when climate change is in the picture, things become much more complex.

To keep abreast of what’s happening, the President has a platform in his situation room that tracks drought and its effects on agriculture in real time. It was developed by Pulse Lab Jakarta (PLJ), a big data analytics lab which emerged from a partnership between the United Nations and the Government of Indonesia.

Derval Usher, PLJ’s Head of Office, hopes to support development and urbanisation efforts through “better use of data and new digital data sources”. “People are starting to understand the use of evidence for policymaking, and the better use of new data sources for solving inherent problems,” she says.

Usher shares with GovInsider four ways PLJ is using big data analytics to help Indonesia and other countries address development issues.

1. Getting ahead of drought

Over 22 million Indonesians rely on agriculture for their livelihood, according to the UN, and the El Niño climatic event, which brings oscillating extreme temperatures, led to drought in several districts last year.

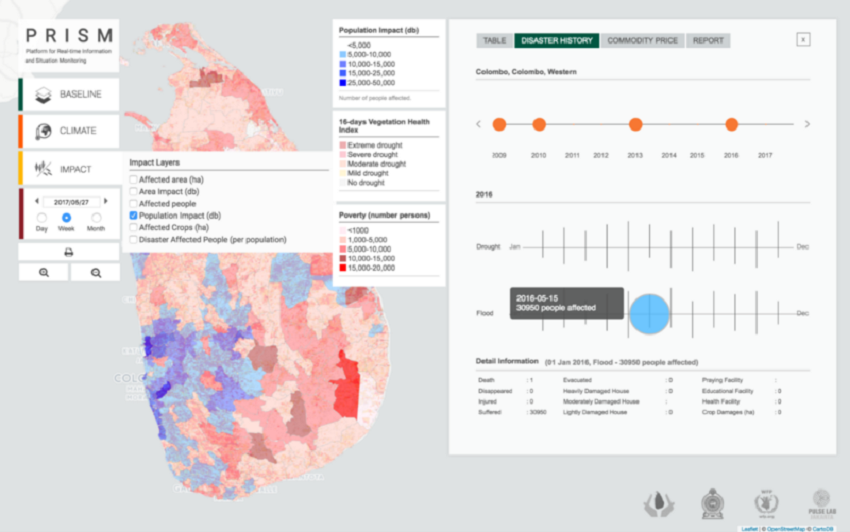

PLJ joined forces with the World Food Programme (WFP) and the Food and Agricultural Organisation to develop a platform that identifies affected communities in need of help, says Usher. The VAMPIRE visualisation tool combines data in several layers: users can view where food-insecure and agriculture-dependant communities live; data on rainfall anomalies and vegetation health; and crowdsourced prices of staple foods in these areas.

The Indonesian government can take a closer look at how drought is affecting crops, and adjust their response accordingly, Usher explains. “You start to see that it hasn’t rained in some time, and food prices are going up.”

She adds that VAMPIRE, which is installed in the President’s situation room, is “an early warning system” for authorities to manage food security and better allocate resources. Following VAMPIRE’s success in Indonesia, WFP is now in discussions with the Sri Lankan government to have it installed there too, Usher shares.

2. Haze be gone

Environmental issues are another area where data analytics can help, especially when these issues are transborder ones. The annual blight of the haze is a sore spot for Indonesia – and its often-disgruntled neighbours.

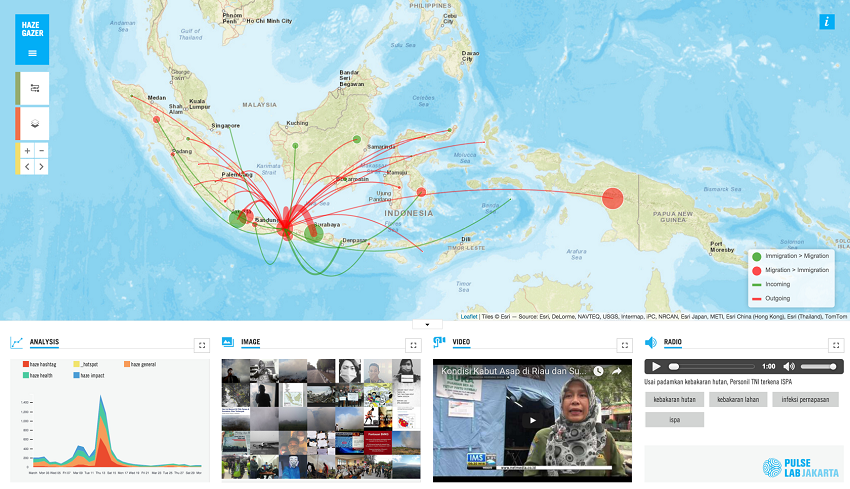

PLJ set out to use data to help locate the agricultural fires that are to blame. “We’ve developed a platform [which] started off as a social media project to see whether we could capture, map out instances of fires in Indonesia,” Usher explains.

Essentially, the Haze Gazer platform helps disaster management authorities to provide quicker responses, Usher says. It is also installed in the Indonesian President’s situation room, she adds, “so you’ve got the citizens reporting directly into the President’s situation room”.

The PLJ team drew from various sources of publicly-available social media data, such as tweets, Instagram posts and Youtube feeds, and combined them with satellite imagery to create a dynamic visualisation tool. They also trawled the internet for the keywords kabut asap (haze in Bahasa Indonesia) and if they were used together with phrases related to poor health or not going to school. “You can get the citizen impact of haze,” Usher explains.

3. Crowdsourcing translations

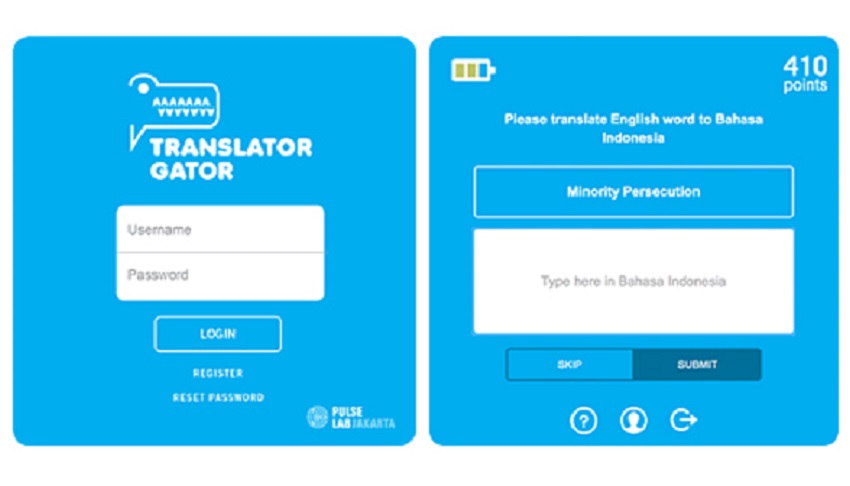

Data analytics can help governments speed up their response in the event of a disaster. Translator Gatoris an online language game – a “brainchild of our data science team”, Usher says – that invites people to create taxonomies, or collections of keywords, in lesser-known languages and dialects.

Eventually, these crowdsourced taxonomies can be used to better understand how affected populations are responding to a disaster on social media and other channels, according to a PLJ blog post on the UN Global Pulse website. Response teams will also be able to better communicate with them. This is particularly important for countries such as Indonesia, where there are several local dialects and even slang.

How it works is that users can choose to translate disaster-related keywords and phrases from English to their native language; evaluate others’ translations; suggest alternative words or phrases; or classify words and phrases into categories, says Usher. “It was a playful game where we were incentivising people and offering them phone credit for every translation that they gave us.”

Translator Gator proved so successful that PLJ extended the initiative to ten ASEAN countries and Sri Lanka, according to Usher. The second phase just wrapped up this year, and at last count, there were over 1.8 million activities across the 11 countries, she adds.

The project has caught the attention of other countries in the region as well. Thanks to the “overwhelming success” of Translator Gator in Vietnam, PLJ has been approached by UN colleagues in Vietnam to extend the competition, and include more ethnic languages than originally planned on, Usher shares.

4. Data for better transport

Jakarta is the “tweeting capital of the world”, and all of that social media data poses interesting possibilities for unconventional use. PLJ is working with the Jakarta Smart City Unit to analyse publicly-available tweets of commuters taking TransJakarta buses, which can help improve on urban planning and decision-making around transport, Usher says.

“We are looking at better optimisation of the buses based on where people are getting on the buses in the morning; where they are starting off their journey; where are they getting off; what are peak times for people to travel,” Usher explains.

Interestingly, the Indonesia Institute of Statistics carried out a study in 2014 that looked at the origins and destinations of commuters in Jakarta, and “the official statistics are very similar to what came through on Twitter,” Usher notes.

Certainly, mining tweets is “a lot cheaper than doing a costly survey”, she believes, and in a “fast-moving” city like Jakarta, the situation could turn out very differently in the five years before the next survey.

All things considered, “big data can give you a ‘snapshot’ of what’s happening on the ground this time, rather than relying on data collected maybe five years ago,” concludes Usher, and “complement the traditional statistics” that are already available.

With data, governments can respond faster and more efficiently to drought, haze, and other issues as they are happening. As Indonesia urbanises, data is likely to be an essential part of its development journey.