Children eat snacks next to the Jambe river filled with trash and household waste in Bekasi, West Java province on 2 November, 2019. (AFP Photo)

Children eat snacks next to the Jambe river filled with trash and household waste in Bekasi, West Java province on 2 November, 2019. (AFP Photo)

While Southeast Asia is working hard for the shift into completely embracing the Fourth Industrial Revolution, and its citizens are getting excited about such things as blockchain and the Internet of Things (IoT), the region is still struggling with something that mankind has been trying to fight off since the dawn of time – hunger.

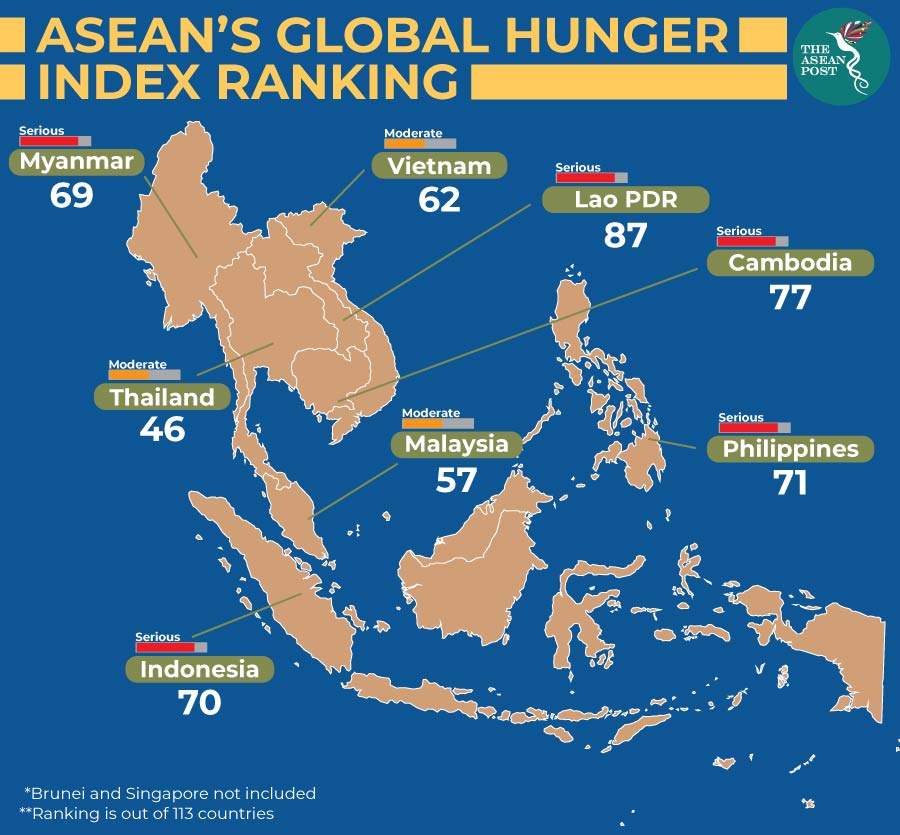

When the Global Hunger Organisation (GHO) revealed its 2019 results for the Global Hunger Index (GHI) it was painfully obvious that ASEAN member states are still relatively hungry. Perhaps with the exception of countries like Brunei and Singapore (which were not included in the survey), even the bloc’s top performer – Thailand – only came in 46th spot out of the 113 countries surveyed.

While remarks for the rest of the world ranged from “low” to “extremely hungry”, only Thailand, Malaysia and Vietnam got away with a “moderate” while the GHI index shows that the state of hunger in Myanmar, the Philippines, Indonesia, Cambodia, and Lao PDR is still “serious”.

Perhaps because of their innocence, it is the children’s suffering – or in this case, hunger – that strikes at the heart the most.

Starving children

The GHI uses four indicators: undernourishment, which is the share of the population that is undernourished or whose caloric intake is insufficient; child wasting, which is the share of children under the age of five who have low weight for their height, reflecting acute undernutrition; child stunting, the share of children under the age of five who have low height for their age, reflecting chronic undernutrition; and child mortality, which is the mortality rate of children under the age of five (in part, a reflection of the fatal mix of inadequate nutrition and unhealthy environments).

Apart from the rankings and its remarks, the GHI also scores countries based on their level of hunger.

According to the GHO, “a GHI value of 0 would mean that a country had no undernourished people in the population, no children younger than five who were wasted or stunted, and no children who died before their fifth birthday. A value of 100 would signify that a country’s undernourishment, child wasting, child stunting, and child mortality levels were each at approximately the highest levels observed worldwide in recent decades.”

ASEAN's global hunger index ranking Source: Global Hunger Organisation

ASEAN's global hunger index ranking Source: Global Hunger Organisation

Back in 2017, a report by the World Health Organisation (WHO), United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) and World Bank Group revealed that more than half of all stunted children, almost half of all overweight children and more than two-thirds of all wasted children live in the Southeast Asian region.

Looking at Southeast Asia, the results are, unfortunately, not too surprising. 25.8 percent of children under five are stunted, while 8.4 percent and 7.2 percent of children under five are wasting and overweight, respectively. Much like the GHI 2017, the 2019 report finds that stunting prevalence is highest in Cambodia and Lao PDR, as well as in parts of Indonesia, the Philippines, and Myanmar.

Causes

There could be numerous factors contributing to hunger in ASEAN countries and these factors could very well vary from country to country. As for the Philippines, Rolando T. Dy, co-vice chair of the MAP AgriBusiness Committee and Executive Director of the Center for Food and AgriBusiness of the University of Asia & the Pacific seems to believe that poverty is a huge contributor.

Dy noted that low income and high food costs generally limit food quantity and quality intake. Citing statistics from the Asian Development Bank (ADB), he pointed out that the Philippines has a far higher incidence of poverty at 21.6 percent compared to its neighbors: Malaysia (0.4 percent), Vietnam (seven percent), Thailand (8.6 percent) and Indonesia (10.6 percent). Myanmar posted 32.1 percent.

“Since two-thirds of all poor come from the farm and fishery sectors, Philippine government policies and programs must address income-raising crop productivity and diversification as well as nutrition,” he said.

According to the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) in its flagship ‘The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2018’ report released in September 2018, while the situation in Southeast Asia is less worrying compared to other regions, a closer look at the subregion reveals that the increase in the number of hungry people in Southeast Asia is mostly due to the adverse effects of climate conditions on food availability and prices. This is opposed to the increase in the number of hungry people in West Asia, which is caused by prolonged armed conflicts.

Whether it’s poverty or climate change, ASEAN – in its zeal to fully embrace the Fourth Industrial Revolution – must keep a close watch at all of its peoples’ wellbeing. Even in Abraham Maslow’s famous hierarchy of needs, shelter and most importantly food make up the pyramid’s foundation. While the Fourth Industrial Revolution is already here, hungry children could scupper its progress.